The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Review

|

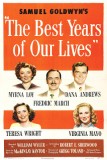

The Best Years of Our Lives

Theatrical Release: November 21, 1946 / Running Time: 170 Minutes / Rating: Not Rated Director: William Wyler / Writers: Robert E. Sherwood (screenplay), MacKinlay Kantor (novel) Cast: Myrna Loy (Milly Stephenson), Fredric March (Al Stephenson), Dana Andrews (Fred Derry), Teresa Wright (Peggy Stephenson), Virginia Mayo (Marie Derry), Cathy O'Donnell (Wilma Cameron), Hoagy Carmichael (Butch Engle), Harold Russell (Homer Parrish), Gladys George (Hortense Derry), Roman Bohnen (Pat Derry), Ray Collins (Mr. Milton), Minna Gombell (Mrs. Parrish), Walter Baldwin (Mr. Parrish), Steve Cochran (Cliff), Dorothy Adams (Mrs. Cameron), Don Beddoe (Mr. Cameron), Marlene Aames (Luella Parrish), Charles Halton (Prew), Ray Teal (Mr. Mollett), Howland Chamberlain (Thorpe), Dean White (Novak), Erskine Sanford (Bullard), Michael Hall (Rob Stephenson), Victor Cutler (Woody Merrill) |

Buy The Best Years of Our Lives from Amazon.com: Blu-ray DVD Instant Video

When World War II broke out, there was no hesitation from the film industry to dramatize it. While the medium was being used for propaganda and boosting morale, narrative cinema also got into the act, putting this global event on display either as backdrop or in the foreground. The war added timely relevance and significance to every film that featured it. This 1946 drama was adapted from the novella Glory for Me by MacKinlay Kantor, an American author who had served as a war correspondent in London and interviewed many U.S. troops. From these interviews and the experiences he observed, Kantor told the poetic story of three men returning to the same hometown following their active duty.

Army platoon sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March), decorated Air Force bomber pilot Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), and double amputee Navy sailor Homer Parrish (Harold Russell) meet for the first time while waiting for a plane. They share one flown by Fred and then a cab that takes them to their respective residences in the fictional Boone City.

Each carries a mix of excitement and anxiety upon returning to their loved ones. Al is coming home to his wife of twenty years (Myrna Loy, top-billed out of stardom, not screentime) and their two mostly grown children. Fred is reuniting with Marie (Virginia Mayo), the blonde bombshell he married shortly before shipping out. And young Homer gets to see his fiancιe Wilma (Cathy O'Donnell) and introduce her to his new hook hands.

Civilian life is an adjustment for each of these veterans. Al takes to heavy drinking as he reluctantly accepts a promotion at his old bank to loan officer assigned to serve G.I. Bill-seeking veterans. Fred finds that his wife isn't all that attracted to him out of uniform and out of money, which he is after struggling to find work with no relevant skills. Handicapable Homer has to come to terms with children's fears and mutterings as well as his own dependency, growing reclusive and avoiding his gal.

While some of these romances are rekindled, a new one sprouts up between Fred and Al's young adult daughter (Teresa Wright), which Al expectedly disapproves of on its extramarital nature.

At 170 minutes, Best Years sounds epic and potentially laborious, but it is actually a fast and enjoyable viewing. This is unquestionably the definitive post-war film and reveals post-war to be as dramatically compelling as, if not more than, war itself. It's amazing how quickly this film came together to recognize this predicament and call attention to it. The war ended at the beginning of September 1945 and here was Best Years opening in theaters a week before Thanksgiving 1946. Kantor and Robert E. Sherwood, the scribe who loosely adapted his story, produced something of resonance and beauty. Sixty-seven years later, those qualities remain on full display. This film may have been a perfect reflection of a moment in time for much of the world, but director William Wyler and his cast immortalize that moment for all ages in a tasteful and nimble way. This isn't like Wyler's Mrs. Miniver (1942) assuming brief importance because of its message and timing. This is a film that endures because its subject is humanity, one that will never go out of style.

A product of a decade marked by message movies that won raves for overdramatizing current issues like antisemitism (Gentleman's Agreement) and alcoholism (The Lost Weekend), Best Years avoids that type of fleeting significance by giving us a number of challenges facing new veterans and not hitting us over the head with them. Sure, the issues are neatly delineated and somewhat sanitized per the period's standards. Al has a little too much to drink, but isn't in any real danger. Fred has to settle for working a perfume counter under his old assistant, but it doesn't seem all that bad. Homer's struggle with his disability is mostly in his own head. Instead of one of these issues being magnified and centralized, they're all present within believable routine activity and serve to develop palatably a good-sized ensemble cast.

Any questions of realism are pretty much eradicated by the casting of Harold Russell, a real life war veteran and double amputee. Not really an actor (although he did lose his hands while making an Army training film), Russell's comfort and skill with his prosthetic hooks cannot be faked. The reality of his handlessness heightens his character's story and adds dramatic power to his every moment onscreen. That Russell can actually act too, with the best of his castmates, ensured he would be recognized. To date, his is the only performance to win two Academy Awards; it won both an honorary award "for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans" and the Best Supporting Actor in ordinary competition.

Those were just two of the film's nine Oscar victories. It also won for Best Picture, Director, Actor (Fredric March), Screenplay, Editing, and Score of a Dramatic or Comedic Picture, plus an Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for producer Samuel Goldwyn. Well before securing these accolades, Best Years had already found great commercial success stateside and abroad. Its grosses were the highest since Gone with the Wind. Though its $11.3 million domestic haul translates to a far from earth-shattering $131 M by plain US currency inflation, it sold an estimated 55 million tickets, comparable to the first Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings installments and very few films since then, despite the US's population having doubled since the '40s. Adjusting for movie ticket inflation, Best Years presently ranks 75th of all time, with a $443 M domestic gross that easily bests all of 2013's output.

Having been released to DVD by HBO in 1997 and MGM in 2000, Best Years joined the massive Warner Home Video catalog in 2012 along with six dozen other classic Samuel Goldwyn productions. Following a new DVD edition issued in January, Warner gave the film its Blu-ray debut this week, just in time for Veteran's Day.

Watch a clip from The Best Years of Our Lives:

VIDEO and AUDIO Warner treats The Best Year of Our Lives to an extremely strong Blu-ray presentation. The 1.37:1 Academy Ratio video is close to flawless. Hiding the film's considerable age, the sharp, clean black and white picture suffers from nothing more severe than a few missing frames in a single shot. It still looks like a 1940s film, but one that benefits from the best restoration and authoring technology available today. Also satisfying is the only soundtrack option, 1.0 DTS-HD master audio. The monaural mix isn't flashy, but it gets the job done. Dialogue remains crisp and complemented by Hugo Friedhofer's appealing score throughout, while distortion and hiss are kept to an absolute minimum.

BONUS FEATURES, MENUS, PACKAGING and DESIGN

I had to do a double take regarding the Blu-ray's bonus features. That's because, although Warner is renowned for their loaded releases of classic films and their press information indicated a whopping 430 minutes of bonus content, this one gets just the same three extras it got on DVD, adding up to only ten minutes of content, all of it still in standard definition. The first two items seem to date back to 1997's HBO-distributed "Special Edition" DVD. There is an introduction to the film from actress Virginia Mayo (1:10). Then, an interview lets Mayo and co-star Teresa Wright discuss their favorite and least favorite scenes. Mayo also shares a nitpick and recalls filming this in tandem with The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Beyond that, all we get is Best Years' original theatrical trailer (1:48), a welcome but unremarkable inclusion that declares the film "The Best Thing That Ever Happened." The disc's static, silent menu simply offers a wide 16:9 rendering of the recycled cover art. The disc resumes playback but does not let you set bookmarks. No slipcover or inserts accompany the eco-friendly keepcase and its plain black labeled disc.

CLOSING THOUGHTS The Best Years of Our Lives makes its Blu-ray debut with less fanfare than you'd expect. Though the lack of new and/or more substantial bonus features might disappoint and surprise given the film's stature, Warner's terrific feature presentation leaves nothing to be desired. That combined with the quality of the film is enough to make this one of the easiest 1940s movie Blu-rays to recommend. You needn't collect Best Picture winners to want to give this classic a spot on your shelf. Buy The Best Years of Our Lives from Amazon.com: Blu-ray / DVD / Instant Video

|

Related Reviews:

DVDizzy.com | DVD and Blu-ray Reviews | New and Upcoming DVD & Blu-ray Schedule | Upcoming Cover Art | Search This Site

DVDizzy.com Top Stories:

New: From Here to Eternity I Married a Witch Mad Men: Season 6 The Big Parade Cinerama Holiday My Name Is Nobody

Best Picture Winners on Blu-ray: Wings On the Waterfront The Apartment Lawrence of Arabia Titanic Argo

Adapted by Robert E. Sherwood: Rebecca | Directed by William Wyler: Funny Girl | Teresa Wright: The Rainmaker

Classics on Blu-ray: It's a Wonderful Life Sunset Blvd. Beauty and the Beast (1946) A Letter to Three Wives House of Wax

Text copyright 2013 DVDizzy.com. Images copyright 1946 Samuel Goldwyn and 2013 Warner Home Video.

Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.