| <- Previous 3. All Quiet on the Western Front |

4. Cimarron (1931) | Next -> 5. Grand Hotel |

|

Cimarron

Theatrical Release: February 9, 1931 / Running Time: 123 Minutes / Rating: Not Rated Director: Wesley Ruggles / Writers: Howard Estabrook (screen version); Edna Ferber (novel) Cast: Richard Dix (Yancey Cravat), Irene Dunn (Sabra Cravat), Estelle Taylor (Dixie Lee), Nance O'Neil (Felice Venable), William Collier, Jr. (The Kid), Roscoe Ates (Jesse Rickey), George E. Stone (Sol Levy), Stanley Fields (Lon Yountis), Robert McWade (Louis Hefner), Edna May Oliver (Mrs. Tracy Wyatt), Judith Barrett (Donna Cravat), Eugene Jackson (Isaiah) |

Cimarron is among the most curious of Best Picture winners. 1931 has its fair share of films still highly regarded today: gangster flicks The Public Enemy and Little Caesar, Universal's horror classics Frankenstein and Dracula, comedies from Charlie Chaplin (City Lights) and the Marx Brothers (Monkey Business), the best-known filming of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (starring a statue-winning Fredric March), and Fritz Lang's M. You'll have to look hard for fans of Cimarron, whose 6.2 IMDb rating is the lowest of any Best Picture winner and whose 3-star Amazon customer rating is a half-star shy of Daddy Day Camp's. Based on the popular novel by oft-adapted author Edna Ferber (Show Boat, Giant), Cimarron tells the story of a family who settles in a small pioneer town in the territory of Oklahoma.

Filled with wanderlust, paterfamilias Yancey Cravat (played by the wonderfully-named Richard Dix), his wife Sabra (Irene Dunne), and their young son leave the comforts of Wichita behind for a new life in the south-midwest. Yancey soon realizes his newspaper aspirations but must endure local threats while providing for his family. When his wanderlust returns, Yancey essentially abandons his family. And he's the hero of this piece.

The vast majority of Wikipedia's article on this film deals with its portrayals of ethnic minorities. Many have deemed Cimarron offensive in this regard and the word "racist" inevitably arises in discussions. The most common target of such complaints may be Isaiah (Eugene Jackson), who no doubt earns my interesting supporting character title here. The Cravats' uneducated, prematurely-mustachioed young black servant pops out of a bag, revealing himself to have secretly made the westward journey with the family. Mrs. Cravat is no fan of the Native Americans, even as her husband stands before a non-denominational congregation and recognizes that only Indians are excused from contributing to the community collection, on account of their land being stolen. Mrs. Cravat faces her prejudices head on when her son takes an interest in an Indian member of the family's hired help. There is also a Jewish character named Sol Levy (George E. Stone), who is none too subtly thrust up against a cross by gun-slinging bullies. The peddler becomes Yancey's editor and part of the extended family.

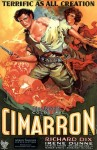

Fans of the Western must cringe at having this be one of the genre's few Best Picure winners. Many more, regardless of their tastes, watch Cimarron and just cringe. Most modern viewers might welcome some subtlety in Richard Dix's crude lead performance, which somehow reminded me of Johnny Cash at his most impetuous. Despite his progressive thinking, Yancey is not an easy character to like, as he inexplicably drifts out of the picture and his family's life, his whereabouts and survival unknown. It would be one thing if the film didn't idolicize the character, but one look at the movie poster's nipple-bearing hero pose and you know that's not so.

This film is interested in and seemingly quite enamored with America's westward expansion, a period that unbelievably was only as distant to Cimarron's first viewers as the moon landing currently is to us. That reality sets in when the film announces its setting as 1930 and its characters are still kicking.

While much of Cimarron doesn't stand up to criticism, I must confess to getting a kick out of its opening credits, which have the cast of characters taking turns posing in front of a black screen while their parts are announced like a 1970s sitcom.

Cimarron may have won Best Picture, but it lost a whole bunch of money for RKO Radio Pictures, which had spent over $1 million on the film including a then-record-high $125,000 for the rights to Ferber's novel. Today's obvious criticisms are less responsible for the flop performance than the Great Depression, which hit America in the months prior to the film's release. The financial failure didn't prevent MGM from remaking the film in 1960, with Glenn Ford and Maria Schell as the Cravats.

In several scenes of Cimarron, it looks like it's raining inside the Cravat house. It's not a leaky roof but an unsightly DVD transfer that's to blame. Though Warner calls this 2006 release a Special Edition, there isn't much that's special. The only extras are a couple of shorts, one of which is a forgettable living toys cartoon called Red-Headed Baby. Much more interesting is the 16-minute 2-strip Technicolor musical comedy The Devil's Cabaret in which Satan has his showman helper (Edward Buzzell) try to lure more people to Hades with nightclub acts.

Cimarron rating: 5.5 out of 10 - Buy from Amazon.com

Previous: All Quiet on the Western Front / Next: Grand Hotel |

Related Reviews:

Little House on the Prairie (2005) • One Little Indian • Home on the Range

Walt Disney Treasures: Mickey Mouse in Black & White, Volume Two

The Apple Dumpling Gang • The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin

Best Picture Oscar Winners | UltimateDisney.com | DVD and Blu-ray Reviews | DVD & Blu-ray Schedule | Upcoming Cover Art | Search This Site

UltimateDisney.com/DVDizzy.com Top Stories:

Published April 14, 2010.

Text copyright 2010 DVDizzy.com. Images copyright 1931 RKO Radio Pictures and 2006 Warner Home Video.