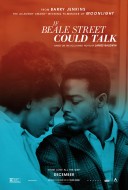

If Beale Street Could Talk Movie Review

|

If Beale Street Could Talk

Theatrical Release: December 7, 2018 / Running Time: 119 Minutes / Rating: R Director: Barry Jenkins / Writers: James Baldwin (novel), Barry Jenkins (screenplay) Cast: Kiki Layne (Tish Rivers), Stephan James (Alonzo "Fonny' Hunt), Colman Domingo (Joseph Rivers), Teyonah Parris (Ernestine Rivers), Michael Beach (Frank Hunt), Aunjanue Ellis (Mrs. Hunt), Dave Franco (Levy), Diego Luna (Pedrocito), Pedro Pascal (Pietro Alvarez), Emily Rios (Victoria Rogers), Ed Skrein (Officer Bell), Finn Wittrock (Hayward), Brian Tyree Henry (Daniel Carty), Regina King (Sharon Rivers), Ebony Obsidian (Adrienne Hunt), Marcia Jean Kurtz (Italian Grocer) |

Writer-director Barry Jenkins likely had his choice of projects after his second film, Moonlight, won Best Picture at the Oscars two years ago. Rather than opt for something bigger or more commercial, Jenkins has chosen to make If Beale Street Could Talk, an adaptation of James Baldwin's 1974 novel. Like Moonlight, the film is small, intimate, and moving. It also happens to give respectful representation to a cast of complex, predominantly African-American characters.

Our focus is on a couple in Harlem in the early 1970s. Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) have been best friends since childhood. Now, they are partners in a committed relationship. Theirs is a pure love, purer than any other to occupy the screen this year. But it is also a strained love. One reason for that is their two families do not get along, Fonny's mother (Aunjanue Ellis) being a judgmental woman of faith who doesn't think the sweet, guileless Tish is good enough for her son.

A more significant source of strain is the fact that Fonny is going to jail. He has been falsely accused of rape and is seemingly on a path to a wrongful conviction, with the accuser disappearing and his alibi getting arrested. Tish's family is doing all they can to mount a formidable legal defense for their would-be son-in-law. They've hired an educated white lawyer (Finn Wittrock), who does seem to believe in Fonny's innocence and want to see justice served. And they're all working hard, or stealing hard in the case of Tish's father's (Colman Domingo), to raise the funds needed for the case and to send a private investigator to Puerto Rico, where the plaintiff has reportedly returned.

The film jumps around chronologically. Our introduction to the couple comes as they are ready to part, though the significance of the parting is not yet known. A bit later, Tish reveals to Fonny that she's pregnant. She's hopeful and confident that the father will be out of prison by the time the baby is born, but we come to see that there's more hope than confidence.

While Tish's family is guardedly excited about her pregnancy, Fonny's mother receives the news with no shred of tolerance or acceptance. We kind of assume that the narrative will pursue this thread, with the two families' patriarchs as amiable drinking buddies and the women of the two clans barely able to be in the same room. But the movie doesn't really follow through on this premise. Nor does it linger on Tish's pregnancy, saying what it needs to on that with one nightmare and the occasional glimpse of protruding belly bump.

Instead, Jenkins' screenplay and presumably Baldwin's text flesh out the romance being torn apart. There's the first time they sleep together, the day and night of the incident (which seems to remove any doubt that Fonny might be guilty), their challenging quest to find a suitable loft apartment, and an unsettling grocery store incident. In these slices of life, Jenkins manages to say plenty about race in America, about love and its obstacles, and about the failings of the justice system. The filmmaker broaches these touchy topics with the steadiest and most human of hands. Not out on a crusade, Jenkins doesn't resort to caricature or extremes (not that this story involves the boldface racism of Spike Lee's sort of true BlacKkKlansman). He remains fully respectful of both his characters and of viewers and that respect gives the film a weight and beauty that a heavier hand would not.

It helps that even just by his third film, Jenkins has distinctive cinematic gifts. The camerawork in the opening shot, which starts on the couple and as they walk towards the camera it lifts up and follows them from above, sets the tone. As on his first two outings, Jenkins entrusts James Laxton with cinematography to ample rewards. Laxton finds ways to make this narrow family, relationship drama feel as big as it can. There's the conversation between Fonny and his friend/future absentee alibi Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry), who just got finished serving two years in jail for a car theft he didn't commit. The camera slowly pans back and forth and around, as Daniel hints at the lingering, profound horrors of prison in what we recognize as personal foreshadowing for our lead. There's the shot when Tish's loving mother (Regina King) arrives in Puerto Rico looking for the vanished victim, in which Laxton catches the setting sun behind her at just the right moment.

Of course, technical artistry rings hollow without strength in the story and characters. You should have already gleaned by now that Beale Street is plenty strong in both of these areas, its solemn story of heartbreak gradually finding clarity and power. There is a tendency in such tight-knit stories to go too far dramatically, to have characters breaking down and just letting perfect poetry spontaneously flow from their mouths. While I can't speak to the book, I can only assume that Jenkins does it justice by avoiding any temptation of melodrama. What we get here are nuanced portraits of black people in 1970s America that resonate without hysterics or hyperbole. The '70s part almost doesn't even register or matter, because we're well aware that issues of race have not disappeared in the half-century since. We're also aware that Jenkins' principal task here is as storyteller and there's no soapbox in sight as he fills that position with tremendous grace, restraint, and authenticity.

In a different year, Beale Street would make for an easy return for Jenkins to the major awards contention of his last film that culminated with both the biggest blunder and the biggest upset in the 90-year history of the Oscars. This year, Jenkins is but one of many gifted filmmakers addressing the African-American experience and how it has or hasn't evolved. To me, this tender, soulful drama is far more deserving of both major and minor nominations than the two presumed contenders with "Black" right in the title. Like Lee and Ryan Coogler, Jenkins has not won Best Director before (La La Land actually did win that one, for Damien Chazelle). Unlike them, he has been nominated and very recently.

Another factor to consider is how much the public embraces this film. Beale Street is only the sixth film distributed in theaters by Annapurna Pictures. Four of those were flops and the fifth -- apparent outlier Sorry to Bother You -- still sold but a fraction of BlacKkKlansman's tickets and grossed less than what Marvel's Black Panther made in its first few hours of showings. Annapurna is rightfully staggering Beale Street's release, expanding it as the expectedly warm word of mouth grows.

Right now, one of the biggest questions regarding the Oscar nominations that will be announced in less than two weeks is whether there will be eight Best Picture nominees or nine. The difference could be the difference between this making the Best Picture field or not. It would certainly be a more welcome sight there than the dramatically underwhelming The Favourite and the putrid Green Book.

|

Related Reviews:

DVDizzy.com | DVD and Blu-ray Reviews | New and Upcoming DVD & Blu-ray Schedule | Upcoming Cover Art | Search This Site

DVDizzy.com Top Stories:

Now in Theaters: Roma • Green Book • The Upside • Vice • Widows • Mary Poppins Returns • Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse • Capernaum

Written and Directed by Barry Jenkins: Moonlight

Fences • For Colored Girls • Black Panther • BlacKkKlansman

Text copyright 2019 DVDizzy.com. Images copyright 2019 Annapurna Pictures, Plan B Entertainment, and Pastel Productions.

Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.