Pixar has a well-deserved reputation for dudes — movies focused on dudes (20 out of 24 feature films), movies directed by dudes (23 of 24), movies written by dudes (50 of 59 screenwriters). But the Disney-owned animation studio has been

trying to evolve, largely because many of its own artists have demanded it.

“Get some ladies!” Domee Shi told me recently. “Draw from different creative wells!”

Shi, who likens herself to a cat oscillating between “lazy and grrr,” arrived at Pixar as a storyboarding intern in 2011, when she was 22. She stayed on as a staff artist, contributing to films like “Inside Out” and “Incredibles 2.” In 2018, she became the first woman to direct a Pixar short. That eight-minute movie, “Bao,” about a dumpling that comes to life, giving an aging Chinese woman relief from empty nest syndrome, won Shi an Oscar — and put her on course to break an even bigger glass ceiling at Pixar.

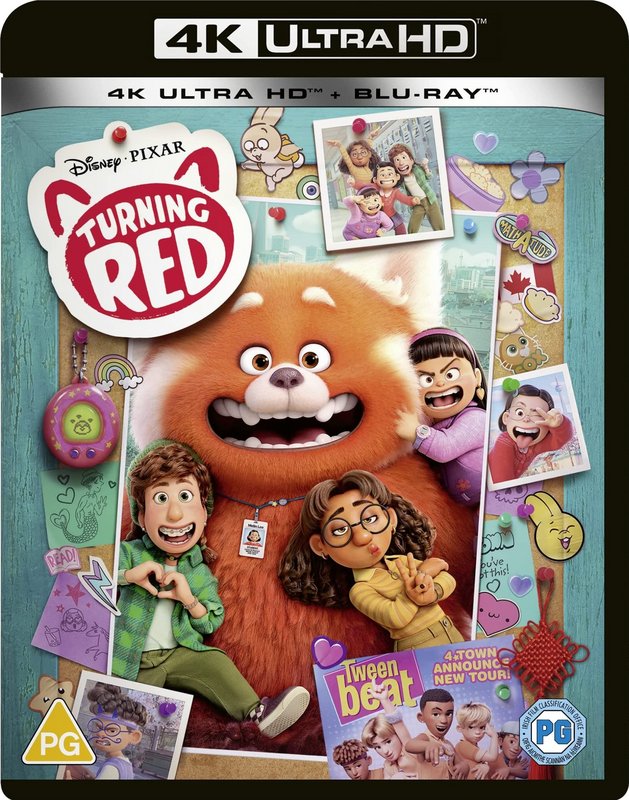

The studio’s 25th feature, “Turning Red,” will arrive on Disney+ on March 11. Shi directed it, the first woman in the studio’s 36-year history with that solo distinction. (Brenda Chapman was hired to direct “Brave” (2012), about a defiant princess in ancient Scotland, and retains a credit. But she was fired during production for “creative differences” and replaced by a dude.)

Moreover, “Turning Red” tells an unabashedly female story — so much so that it reads as a corrective to the Woody-Buzz-Flik-Sully-Mike-Mater-Lightning-Luca bromances in which Pixar has specialized.

...

About a decade ago, Disney and Pixar started to routinely showcase different cultures, races and ethnicities. The success of “Big Hero 6” (2014) and “Moana” (2016) led to diverse films like “Coco,” “Raya and the Last Dragon,” “Soul” and “Encanto.” Some of those same movies continued to break down gender stereotypes by depicting bold, brainy women who didn’t need a man’s love to make them whole. (Credit to “Brave” for fostering that change.) Pixar also began to embrace progressive storytelling in its short films, most prominently with “Out,” about a man who decides to stop hiding that he is gay.

But adolescent sexuality and the biological changes that come with it have remained a third rail. Some slight innuendo? Maybe. Anything more might spook conservative parents and threaten Disney’s family friendly brand.

“How do I sneak this through?” Shi recalled thinking before one pitch meeting with senior Walt Disney Studios executives. “How do I sell this and get old white men who’ve never experienced this before excited about this and wanting to, like, see more of it?”

Disney, which, like other Hollywood studios, had been espousing female empowerment in response to the #MeToo revolution, put its money where its mouth was: In spring 2018, the company gave Shi a budget of roughly $175 million to tell her story, along with the backing of its merchandising and marketing divisions.

“I felt like they were always in my corner, even if they sometimes were, like, whaaat?” Shi said.

At the time, Pixar was in turmoil. John Lasseter, the studio’s chief creative officer, had been placed on leave following complaints about inappropriate workplace behavior. Others blasted Pixar for sidelining women and people of color. Lasseter apologized for “missteps” and resigned in June 2018.

The Pixar filmmaker Pete Docter (“Up,” “Inside Out”) was handed the studio’s creative reins, which was fortuitous for Shi, since Docter had helped shape her unconventional “Bao.”

The short has an offbeat ending that is meant to symbolize the all-consuming love of a parent: The older woman abruptly eats the dumpling, little legs and all. It was the ending that Shi wanted all along, but she had chickened out when first pitching the story to her bosses. “I worried that eating the dumpling was too dark and weird and confusing and totally not something Pixar would go for,” she said. So she pitched a safer option.

“Pete was in that pitch meeting,” Shi recalled, “and he stood up and said, ‘Wait, no, that is not the version you told me about a couple weeks ago.’ He turned to the group and said, ‘Her original ending was really cool and weird and shocking.’”

Shi was allowed to re-pitch, this time with her idea intact. “I think because of that experience it gave me the confidence to not be afraid to try bold, weird and shocking things in the stories I want to tell — to not censor myself,” she said. (“Domee knows that surprise is something we all crave in stories,” Docter said in an email. “We don’t want to be able to predict where things are going. And with Domee, I find that is often the case — both in her work, and as a person!”)

“Bao” won the 2019 Oscar for best animated short. In her acceptance speech, Shi implored “all the nerdy girls out there who hide behind their sketchbooks” to tell their stories. “You’re going to freak people out,” she said, “but you’ll probably connect with them too.”

“Turning Red” has already stirred both reactions. On Twitter, people have been celebrating Mei’s story as long overdue. “Finally, my anxious Asian girl representation,” one user wrote. The Pixar film has also sparked a wider conversation about how periods are portrayed by Hollywood in general. (Usually with a fair amount of shame and disgust.)